ARTICLE – One of the greatest technological advancements of our era is the lithium battery. First prototyped at Exxon in 1976, lithium technology has made it possible to pack a whole lot of energy into a tiny package, enabling more powerful computers, cordless tools, equipment, appliances, human transport devices, and toys. If you have a cell phone, you have a lithium battery in your home. Most rechargeable products on the market today use various forms of lithium battery technology.

Lithium batteries may be everywhere, but does that mean they’re safe? This is an important question that I think has been overlooked across every battery-powered consumer industry, so let’s dive in.

A battery is an energy store

No matter what application, batteries contain energy, and sometimes, it’s a lot of energy. If you’ve ever licked a 9V alkaline battery (do kids still do that these days…?), the tingle is the discharge of the battery’s stored energy through your tongue. The higher the load, the more energy a battery must store. Anything with an electric motor, a pump, or a heating element is likely to be a high-load device, requiring batteries that store a lot of energy.

Our battery-powered energy needs keep expanding, too, and this has required engineers to find ways of packing even more energy into a small form factor. The aggressive government push worldwide to force EV (electric vehicle) adoption has predictably exposed the real, practical flaws with EVs. Range is one of the biggest pain points for existing and potential EV owners, and engineers are constantly looking for novel ways to pack more energy into EV batteries. Most recently, researchers in South Korea prototyped a high-density lithium battery formulation that adds up to 40% more energy to a pack.

Regardless of the technology used, all batteries are energy stores. Your battery contains an enormous cache of energy, waiting to be used by a compatible device. If something bad happens, and the battery is unexpectedly discharged, the consequences can be disastrous, and there is certainly a correlation between the severity of those consequences and the amount of power stored by the battery.

How do batteries fail?

There are several types of batteries common in the average household: alkaline, nickel-based, lithium-based, and lead acid. Small alkaline and nickel-based batteries pose no fire hazard to consumers. The worst incident that might happen with a 3V or 9V battery is corrosion from leaking acid, which is slightly unhealthy but otherwise nonthreatening. That said, it’s important to remove alkaline batteries from something that won’t be used for awhile, because old batteries do leak, and the acid is corrosive. I have a ruined original Apple Magic Trackpad thanks to leaking acid corroding the aluminum enclosure and seizing the threads of the battery cover. Lesson learned!

Lead acid batteries are very common in the average household. Your internal combustion vehicle uses a 12V lead acid battery to start the electrical system that controls the engine, fuel system, and alternator. It requires quite a bit of energy to accomplish this – a 12V car battery generally has a capacity of 550-1000A, which is why jumper cables spit out a sizeable spark when the clips are improperly touched together.

Similar 12V lead acid batteries are common in telecom boxes (including the box your phone company manages for a traditional landline phone) and UPS (uninterruptible power supply) boxes for home and office use. In the case of the latter, these batteries can only supply 10-30 minutes of power to connected computers and other devices, and they’re meant for either safely shutting things down in a power outage, or providing temporary power in the momentary break between an outage and starting your backup generator.

Lead acid batteries most often start fires due to electrical short. In the case of a short, the battery improperly rapidly discharges across whatever’s connected to it. This leads to electrical wires overheating, which in turn ignites the polyvinyl insulation wrapped around the wire. Plastic is derived from fossil fuels, and, once ignited, burns slowly and over a long period of time. As the plastic burns, everything nearby ignites, and an unnoticed battery short under your car’s hood becomes a devastating house fire. A more recent example of this is Toyota’s 2023 recall of nearly 1.9 million RAV4s due to a QA failure that could lead to the battery shorting and starting a fire – which sadly happened at an apartment complex in Honolulu, Hawaii in January 2024.

In terms of vehicle batteries, a serious front-end collision can cause the battery to explode, but this is uncommon, and the fireball you see at the point of impact in such a collision is from the fuel igniting, not the battery exploding. Exploding batteries pose more of a risk from shrapnel and corrosive acid than the energy discharge itself. If you don’t make a habit of rewiring your car’s electrical system, you’re at very low risk of ever experiencing an exploding car battery. If you do work on your own cars and build cars, proper wiring and circuit design is critical to ensure safe battery operation. You can read much more about lead acid battery safety and hazards here.

Why are lithium batteries different?

Now let’s look at the star of this show: lithium batteries. This includes all forms of lithium batteries – lithium ion, lithium polymer, and any other technology relying upon lithium. The single biggest practical reason why lithium is now everywhere is simple: a lithium battery of the same physical size as any other rechargeable battery technology stores significantly more energy. This is what has powered the proliferation of small, cordless electric motors in your power tools, lawn equipment, vehicles (such as hoverboards and e-bikes), and toys.

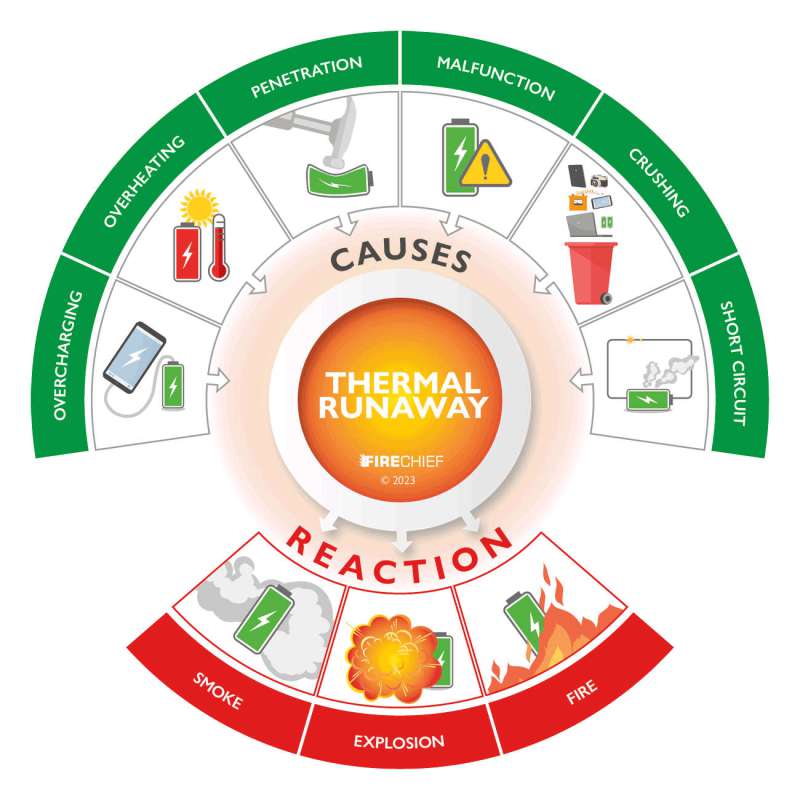

Unlike other consumer battery solutions, the primary fire risk inherent to lithium batteries is a reaction called thermal runaway. This can occur from shorts, as well as when the battery overheats and ignites – something that can happen from overcharging. Once the battery ignites, the energy contained in the battery is discharged very quickly, which creates an unusually hot, strong fire. There is a plethora of industry literature and white papers on the subject of lithium thermal runaway. This is a good place to start if you’re interested in the technical nitty-gritty of this subject.

Not only do lithium batteries contain an extraordinary amount of energy for their physical size, they also contain oxygen, which means a lithium battery fire can feed itself. This is one of the reasons why it is so difficult to extinguish a lithium battery fire. Chemical fires are typically extinguished by depriving the fire of oxygen, using either liquid or dry material. As this article explains in more depth, because lithium batteries contain oxygen, they have what they need to burn, even underwater.

This has created an entirely new set of challenges for firefighters worldwide. Standard fire mitigation protocol doesn’t work with lithium battery fires, because fire suppression is nearly impossible. The only real strategy with a lithium fire of any size is to isolate the fire from other combustibles until it burns itself out. This is somewhat feasible for consumers when we’re talking about small, compact batteries, but what happens if you’re not at home, or asleep?

Home fires caused by lithium batteries are only increasing, as we have more and more of these batteries in our homes. In January 2024, a man in Nottingham, UK lost his apartment to a fire caused by an exploding e-bike battery. The following April, the Boston Herald published an article on the jump in lithium battery fires in Massachusetts, detailing the challenges firefighters face when called to a lithium fire. Australian news outlet ABC published a similar article the same day.

Big batteries, big fires

What if your overcharged, overheating, igniting battery is in your car, or attached to the side of your house or pole barn in a large array? We have no way of submerging a wall-sized backup battery array in liquid to contain the fire, and it’s not too difficult to imagine how catastrophic such a fire might be. In April 2023, video footage released through a FOIA request showed a Ford F-150 Lightning EV truck on fire in a lot in Dearborn, MI. In NBC News’ coverage of the incident, they noted that there are currently no lithium fire mitigation and suppression strategies beyond submersion in water. Other outlets, including Jalopnik and Vox, have covered this subject, focused primarily on EV fires.

While EV battery fires are a major threat and concern, other batteries in your home still pose a fire risk. Many people today live in apartments or townhomes, where using a fuel-powered generator (either standby or portable) isn’t feasible. Home battery backups are an increasingly popular solution for people who want backup power, but can’t or won’t use a generator.

If a battery array attached to the side of a building goes into thermal runaway, there’s no way to safely submerge that array in liquid to contain the fire. So far, there haven’t been any major catastrophes caused by whole-building lithium battery arrays catching fire, but this is only a matter of time and statistical probability, rather than an impossibility.

These concerns aren’t theoretical or hypothetical. Both the government and the consumer goods industry are very aware that the thermal runaway risk with lithium battery technology remains a serious concern. Recently, NIST (America’s National Institute of Science and Technology) issued a press release on research into using AI to intelligently detect lithium ion battery failures before they become catastrophic. This risk is not going away, because it is so fundamental to how lithium batteries work.

Unfortunately, consumer safety regulations are almost always reactive, rather than proactive, which means we likely won’t see any major changes in the safety requirements imposed on these backup battery products until people’s houses start burning down from them at high enough rate, and we might not even end up with the right requirements implemented to prevent future catastrophe.

Little batteries, little bombs: Lithium battery safety and vaping hardware

Since I started writing this article, more lithium battery accidents have hit the headlines. I’ll confess that I’m an avid reader of the Daily Mail, and they love the tabloid nature of these stories, so I tend to notice when another, new accident makes headlines across both Europe and the Anglosphere. Most recently, in late 2024, a 15-year-old in California suffered horrific, life-altering injuries after a vape pen exploded in his face.

Vaping is a particularly important subject when discussing lithium battery safety. Vapes work by heating up substances to the point of vaporizing for inhalation. The heat this involves necessarily poses a heightened risk to the lithium battery used to power the pen, and the battery (which is often a lithium-polymer pouch inside the pen), rapidly expanding from overheating, transforms the pen into a tiny bomb, filled with glass and metal that turn into very dangerous shrapnel.

For this reason, I switched to the eLeaf iStick Pico, which is a reputable product that uses removable standard 18650 lithium cells, and I only purchase genuine Murata (made by Sony until late 2016) cells. The dangers of even a very small vape pen, when kept directly in front of your face, are significant enough that I strongly recommend spending the money on a quality hardware that uses replaceable lithium cells.

It’s also wise to run your device at the lowest optimal voltage. This is particularly a problem with younger folk, who prefer to vape at a higher voltage to get a stronger effect. The problem is that this means more heat, which means higher risk of battery failure. So, if you know your kids are probably vaping on the sly, make sure to talk to them about this, so they know the risks, and how to prevent really terrible accidents.

Theoretically, reputable brands like Juul are using better engineering and components than random Chinese products, but it is important to always be aware of the hazards presented by all vaping hardware, and to stay very vigilant about early signs that your pen is about to turn into a tiny grenade.

Fire safety is for everyone!

There are some simple things you can do to reduce the possibility of a catastrophic failure in a lithium battery in your home:

- Do not leave high-load batteries attached to chargers once full. The safest habit is to always remove any high-load or high-voltage battery from its charger once full. Generally speaking, high-quality batteries and chargers from reputable OEMs are safer than various cheaper rechargeable consumer products, but if you’re particularly concerned about the fire risk, just remove your batteries when they’re charged, instead of leaving them on the charger. I definitely recommend never leaving high-voltage lawn equipment batteries on standby charging. These batteries contain a whole lot of energy, and while current popular brands have a good track record thus far, any failure – no matter how seemingly improbable – is devastating enough to be vigilant about not leaving these batteries on their chargers.

Never leave high-voltage batteries on the charger once fully charged! - When it comes to products that are likely to be using poorly engineered charging circuits and cheaply-made batteries (like hoverboards and e-bikes), never leave the battery unattended while it is charging. In my research for this article, it’s become clear that motorized mobility toys for teenagers, which often use high-voltage, high-load batteries, are an understated fire risk. Treat a charging e-bike or hoverboard battery the way you would a campfire: it requires constant attention, and you have keep checking to ensure the battery doesn’t overheat, because the possibility of both overcharging and thermal runaway warrants the vigilance.

- Avoid cheap batteries, chargers, and rechargeable products. This is sometimes impossible. I have a lot of old laptops, and can only find third-party batteries for most of them. For this reason, I don’t leave my laptops plugged in indefinitely anymore. OEM laptop batteries are generally not a risk, and the same generally applies to reputable battery brands, like Batteries+. Be very wary of every generic Chinese laptop battery you find on Amazon, eBay, and elsewhere. When it comes to toys and devices with rechargeable batteries – like earbuds, power banks, pocket flashlights, and other things – be wary, and stay alert.

Stick with OEM power tool products. - Try to find products that use replaceable batteries. Double points for devices that use commodity lithium cells of various sizes, because this means you can be certain you’re using quality cells. If this isn’t possible, prefer devices with replaceable batteries over those without. This not only extends the longevity of your electronic devices; it also allows you to more safely deal with a failing, or failed, battery.

- Do not use batteries that have expanded (increased in volume or physical size) at all. An expanding battery is a rapidly failing battery. These batteries are at high risk of explosion and thus shrapnel. Do not use them, do not charge them, and dispose of them at your local retailer that accepts bad lithium batteries. It really is dangerous to landfill and garbage workers to toss these in the trash, so please don’t do it!

The iPhone 8 Plus had a problem with premature battery expansion, causing case separation. Source: PocketNow - Don’t use wireless charging, no matter how cool and convenient it is. The induction field created by wireless charging requires a lot of energy is not very efficient, and the design creates excess heat. I destroyed one of my smartphones awhile back from using wireless charging. The phone overheated, the battery expanded slightly, and it’s never been the same. Stick with regular USB charging, and use a quality multi-port charger with USB-C PD and high-amperage USB A. I’ve been really happy with this one; I use it with my Switch Lite, iPad 9th Gen, Boox Palma 2, and a couple low-power 5V USB devices.

- Do not continue to use rechargeable devices that no longer hold a charge, or only hold a very small charge, especially if you can’t get to the battery. My Philips-Norelco cordless razor, for example, uses a 15V battery to power those fancy little motors. Once the battery’s dying, it’s time to toss it (the factory waterproofing will not be replaceable upon opening to replace the battery, unfortunately), because I’ll have no way of knowing if the battery is expanding to the point of total failure.

- Pay attention to the early warning signs of impending doom. The number one way to prevent accidents of any kind is to maintain vigilance about the hazards.

- If your battery-powered device is very warm or hot to the touch, stop using it immediately. Turn it off, unplug it, and if possible, disconnect the battery. Wait until the device is completely cool before attempting to charge. Pay close attention while charging, and if the battery keeps overheating, it’s time to replace it.

- If the battery in your device is expanding at all, stop using the device immediately. Replace the battery or, if that isn’t possible, the device. This is often discovered when you realize your phone screen or laptop isn’t level anymore. Be aware that devices made of metal and glass are particularly dangerous in terms of battery expansion, because the rigidity of the materials can hold pressure from the expanding battery until an explosion of shrapnel.

A note on device temperature: high-load batteries do get warm as they charge. This is normal, but it means you need to make sure your charging battery – or battery-powered device – has plenty of air space to dissipate that heat. My iStick Pico gets a bit warm when charging, but the shell is metal to dissipate heat more efficiently, so the entire unit acts as a heatsink while the battery is charging. I’ve had my device for four years now, have dropped it a lot, and it’s worked really well with no heat or other charging malfunction concerns. I really don’t recommend dropping it, but so far it’s passed muster for me in terms of battery safety.

Ensuring battery safety across the industry

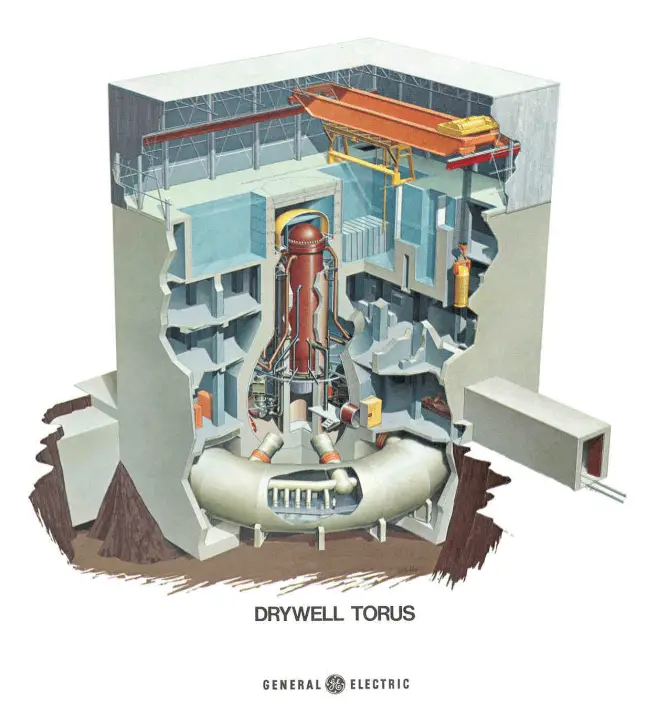

What I’d like to see are backup batteries designed with fire mitigation engineered into the battery. We see this in how modern nuclear reactors are designed to contain (at least partially) a meltdown. The risks posed to the surrounding region by a nuclear reactor meltdown are so serious, the reactor itself contains multiple failsafes to maintain the right conditions. These failsafes are why the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear reactor accident in Pennsylvania was largely contained.

(not representative of Three Mile Island)

We need better containment designs for the lithium battery packs and arrays used to provide backup power to entire houses and facilities. Since it’s impossible to get away from the need to store a lot of energy in a compact space, we need to take seriously the implications of this kind of energy storage. I’m not an engineer, but it seems to me that something akin to a nuclear reactor’s protective shroud is necessary for high-load backup battery arrays. Both fire and shrapnel from explosions are serious risks, and both need to be adequately mitigated.

We may find that certain products are much less feasible when the batteries they use have to include adequate containment in the event of a catastrophic failure. It’s reasonable enough to engineer with something like a backup battery array for a building, or batteries used in EVs, but it’s much harder to accomplish the same feat on the much smaller scale of mobility toys and random rechargeable consumer products. This is a possibility consumers will have to consider, for whatever the future may hold for the safety of lithium battery technology.

Given the hazards inherent to lithium technology, it’s important to emphasize that you should never leave a “backup generator” high-load battery array plugged in and charging either unattended, or over an extended period. Reducing the risk of thermal runaway will protect you from the biggest hazards of big batteries, but the real change needs to come from the consumer product industry, and I hope that change is proactive, rather than tragically reactive.

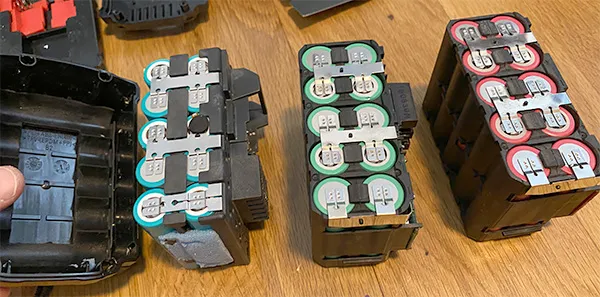

Another aspect of the consumer goods industry I’d love to see change: make battery enclosures with replaceable lithium cells. There are multiple points of failure in a lithium battery charging circuit that can lead to thermal runaway: the charger connected to the battery (either a device or a standalone charger), the charging circuitry in the battery, and the lithium cells themselves are all potential hazards, and all are made more hazardous by the proliferation of poorly-engineered, poorly-made third-party parts and accessories for things like power tools and lawn equipment.

A company like Milwaukee should consider prioritizing consumer safety over the obvious profit margin on only selling replacement batteries. It makes a lot more sense to enable consumers to refurbish their OEM battery enclosures – which are assumed to be designed by competent engineers, be manufactured with quality components, and have undergone adequate QA to identify fatal defects in production – with quality replacement cells, than to force consumers to choose between either overpriced OEM batteries…or cheap aftermarket options that might burn their houses down.

There are plenty of consumer products where user-replaceable batteries are simply not feasible, because the battery is a fragile pouch, rather than one or more standard cylindrical cells. However, power tools and lawn equipment still make use of arrays of commodity cells, so there’s room for updated engineering in these battery packs to make them user-serviceable. This move by a consumer goods industry leader could go a long way toward preemptively and proactively setting a new consumer safety standard that priortizes keeping low-quality imported batteries out of our homes.

If it’s safe and affordable for customers to refurbish their quality lithium batteries with quality lithium cells, we can reduce the possibility of house fires in millions of homes, and give the industry the flexibility to work with self-imposed standards designed around objective safety requirements. I hope to see industry leaders take the initiative to enact needed change, especially as lithium battery fires proliferate in households around the world.

Lead image source: Inside Waste